Scaffolding is Life

We ended the last post in the series with, “Good habits matter to the life of ideas.”

Mason’s third is tool:

“Education is a life. In saying that “education is a life,” the need of intellectual and moral as well as of physical sustenance is implied. The mind feeds on ideas, and therefore children should have a generous curriculum.”

We give our children living ideas to feed their minds. First, it is much easier to teach the habits of attention and interest with living ideas. The atmosphere is more electric and there are more Eureka!s when ideas can bump into each other or connections can be made.

In In Memoriam: A Tribute to Charlotte Mason the Honorable Mrs. Franklin uses a slightly different metaphor (pg 117):

“There is a saying of King Alfred’s that I like to apply to our School,–‘I Have found a door,’ he says. That is just what I hope your School is to you–a door opening into a great palace of art and knowledge in which there are many chambers all opening into gardens or field paths, forest or hills. One chamber, entered through a beautiful Gothic archway, is labelled Bible Knowledge, and there the Scholar finds goodness as well as knowledge, as indeed he does in many others of the fair chambers. You see that doorway with much curious lettering? History is within, and that is, I think, an especially delightful chamber. But it would take too long to investigate all these pleasant places and indeed you could label a good many of the doorways from the headings in your term’s programme.

But you will remember that the School is only a ‘Door’ to let you in to the goodly House of Knowledge, but I hope you will go in and out and live there all your lives–in one pleasant chamber and another; for the really rich people are they who have the entry to this goodly House, and who never let King Alfred’s ‘Door’ rust on its hinges, no, not all through their lives, even when they are very old people.”

Scaffolding is helping our students set foot in that big room through the intimidating door. It’s walking them carefully and intentionally through the galleries and introducing them to the wonders. It’s showing them where and how to connect galleries together. It’s making a map. But they’ll outgrow the need for the map – or they’ll start to draw their own. “I know, I know, mom!” Sometimes they do know. (Admittedly, sometimes they don’t)

Remember how we’re aiming at maturity? This is the stuff that childhood is made of: wonder, imagination, aha! Jesus told us that we had to be childlike to enter the kingdom. Living ideas are the ones that last a lifetime but help us remain childlike in our joy at learning and wonder. They’re the ones that help us to learn about man, the universe, and our God – Mason’s curriculum.

Ideas are the building blocks of the curriculum. They’re placed within easy reach in the right place on the scaffold – but they’re gathered by the child and mortared in place by the child. They pick the one that fits the space they have – which means you cannot pick for them. Whether they pick the William the Conqueror, 1066, or Battle of Hastings block – or all three of them – It’s less important which idea your child chooses that that he chooses. When children narrate they’re making relationships with the ideas and between the ideas in their own mind. (You still have to listen, though)

We talked about how atmosphere affects the meta and the minute. In the meta, the ideas of a curriculum can be scaffolded. It matters that in AmblesideOnline Year 7 we’re reading Beowulf, Birth of Britain, the Venerable Bede, and Asser’s Life of King Alfred together. Does it matter that we read about the Story of the Romans and a biography of Churchill before we read about the Birth of Britain? Of course It does. The curriculum provides context within itself and repetition of ideas helps to cement them into place. Making connections is making relationships.

Which reminds me. We talk a lot about the so-called“riches” in Charlotte Mason circles. Those true and good and beautiful things that man has made over the course of history. Those very things of humanity, those things that add depth and breadth to our understanding of Man, the Universe, and God. So often, though, the way we talk about them is backwards; if we have time, we’ll do picture study. We’ll just listen to our composer while we do other work. Folk songs are extra, we can skip that. This should not be; rather than being “extra” to the curriculum, they are foundational to both inspire a learner’s heart and give something to aspire to. A piece of music, a beautiful drawing, a poem with words that bring tears. The “riches” are what we can love. They exude lifegiving ideas and in my opinion should take precedence of importance because they drive us to write a well turned phrase, or learn about the Fibonacci sequence and the golden mean, or understand fractions on first introduction, or a myriad other ideas in the standard curriculum. Why would we treat these as secondary or less?

We talk about living ideas. Ideas that animate the imagination. Are there dead ideas? Old ideas are not necessarily dead. They may have been proved wrong or may be outmoded, but it’s important to understand geocentrism before heliocentrism. Seeing how ideas were thought plausible but then were disproved and reworked is an idea in itself. Alchemy is an interesting, if wrongly applied idea. But is it a dead idea, or is there something we can learn from it? Even a disproved idea supports the need and reasons for a corrected idea so we and our children can apply and connect ideas – and so we can see how to change course when we’re disproved in our own thinking.

Some ideas might seem uninteresting at first glance, but when we give the structure, the scaffold necessary to it, the idea can capture the imagination. From Volume 1 Mason gives this example:

Children easily simulate knowledge, and at this point the teacher will have to be careful that nothing which the child receives is mere verbiage, but that every generalisation is worked out somewhat in this way:––The child observes a fact, as, for example, a wide stretch of flat ground; the teacher amplifies. He reads in his book about Pampas, the flat countries of the north-west of Europe, the Holland of our own eastern coast, and, by degrees, he is prepared to receive the idea of a plain, and to show it on his tray of sand.

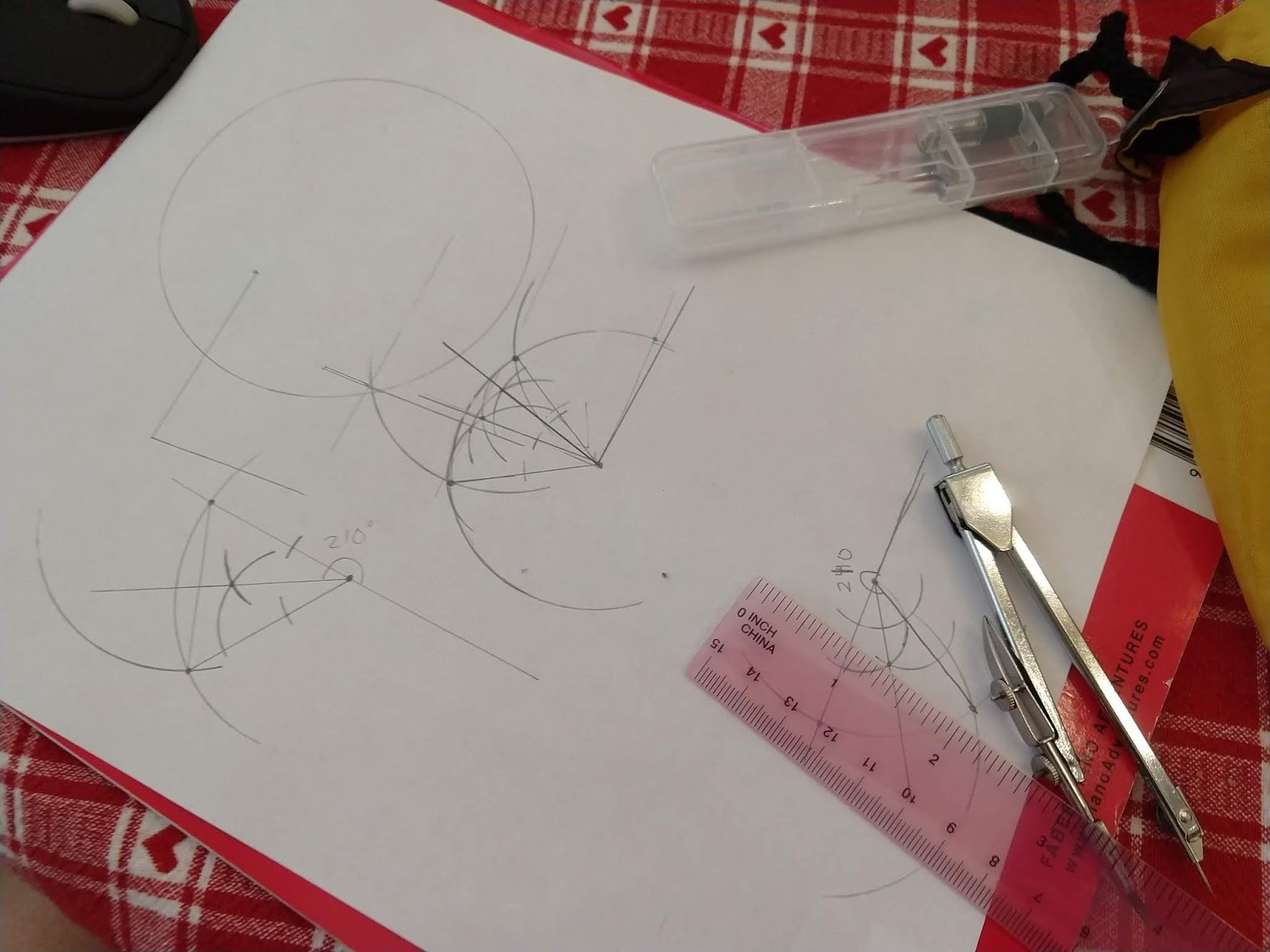

Do you see the structure – a fact, narrated, compared, reconstructed. It’s the same scaffold. Perhaps older children wouldn’t reconstruct in a sand tray but in a nature journal. It may be that this is the step where we talk about the flat parts of Ohio

and compare them to the hilly parts animating a discussion of glaciers and how they work and have worked in history.

And, later, the idea of a “plane” is taken into our studies of geometry

Scaffolding takes living ideas and, when mingled with atmosphere and habit, teaches us how to live. I referred to it before, but from Essex Chomodeley’s biography of Charlotte Mason, she said:

On my arrival at Ambleside I was interviewed by Miss Mason who asked me for what purpose I had come. I replied: “I have come to learn to teach.” Then Miss Mason said: “My dear, you have come here to learn to live.

Supporting our children in their learning, we are teaching them how to live. The learning procedure is the same for children and for teachers … and for parents because we are all born persons and this is just how persons learn anything.

- Scaffolding and the Homeschool Mom

- Scaffolding Provides Safety in Transparent Fashion

- Scaffolding is a Trustworthy Standard

- A Mother’s Scaffolding is Temporary … It’s for a Season

- Scaffolding is Atmosphere, Discipline, and Life

- Scaffolding is Atmosphere

- Scaffolding is Discipline

- Scaffolding is Life ← You Are Here

- Scaffolding in a Lesson

- Scaffolding Under Conditions

- Scaffolding Q&A